Last month’s power outage in Texas is a dramatic example of the risks posed by extreme weather increasingly fueled by a changing climate. It is also an illustration that although these risks are foreseeable and preventable, necessary action is rarely taken to adapt to and prevent major disruptions and hardship.

February 2021 saw record low temperatures across Texas (-19°C recorded in Dallas), causing more than half the state’s electricity generating capacity to fail. The result was dozens of fatalities, 5 days of rolling blackouts, inoperable cell services, broken heating systems, burst pipes, destroyed crops, and food shortages.These systems were vulnerable to extreme temperatures and failed as a result. This storm may end up being the state’s most costly weather event of all time. Why wasn’t Texas adequately prepared?

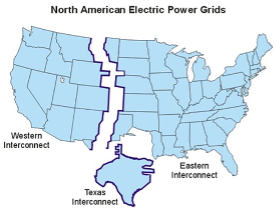

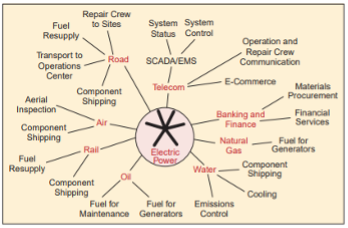

The Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) completed a study three months before the storm to prepare for peak usage, showing the system had sufficient winter capacity. This study did not contain any mention of a changing climate and therefore it is unclear if it was based solely on historic data without considering future climate projections. Numerous reports following previous winter-storm-induced blackouts in 2011 and 2014 produced recommendations to better prepare for disasters, including steps for electricity generation operators to increase winterization. While some upgrades were made, they were not sufficient and didn’t adequately prepare for the extreme conditions seen this year. ERCOT’s own emergency procedures show that their extreme temperature projections were not low enough. The issue was worsened from a lack of system redundancy as the Texas electricity grid is not integrated with its neighbours, and because many critical systems rely on each other and can be disrupted by the loss of one input: electricity (Figure 1).

Unfortunately, due to a changing climate and increasingly extreme weather, disasters like this are expected to be more common in the future. The time to prepare is now.

Figure 1: [LEFT] U.S. Electricity Grid & Markets, U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. [RIGHT] Identifying, Understanding, and Analyzing Critical Infrastructure Interdependencies, figure 2. IEEE Control Systems Magazine, December 2001, Page 14. Rinaldi et al.

Understanding Climate Risk

The Task Force on Climate Related Financial Disclosures (TCFD), commonly acknowledged as the gold standard on climate-related risk disclosure, organizes risks arising due to climate change into two buckets: transition risks and physical risks.

Transition risks are the risks of the economy quickly moving toward a zero-carbon future, with risks arising from associated policy, technology, and market changes. Increasing financial burdens to high-polluting industries from expanding carbon pricing is an example of a transition risk. Our sister company, Manifest Climate, is helping companies dive deep into transition risks to help them understand the latest climate trends and develop strategies to address these risks.

Physical risks are the risks posed from damage to buildings, infrastructure, and systems due to the increased likelihood and severity of acute shocks like floods and wildfire, and chronic stresses like longer-term trends of reduced precipitation or melting permafrost. Reducing climate change-related physical risk exposure to the built environment is one of Mantle Developments’ core focus areas.

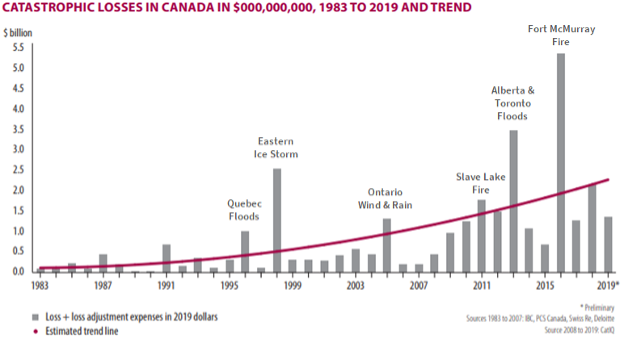

The World Economic Forum publishes an annual report identifying top worldwide risks to the global economy. The 2021 report shows that environmental risks are among the most likely and impactful (Figure 2). Insurance companies know this, across Canada they are already experiencing significant increases to extreme weather-related pay-outs. According to the Insurance Bureau of Canada, catastrophic insurance losses from natural disasters have more than quadrupled from an average of $405 million per year between 1983 and 2008 to over $1.8 billion from 2009 onward (inflation-adjusted, Figure 3).

Figure 2: Global Risk Report 2021. Figure II: The Global Risks Landscape, pg. 12. World Economic Forum.

Figure 3: 2020 Facts of the Property and Casualty Insurance Industry in Canada, page 17. Insurance Bureau of Canada.

Physical Risks to Infrastructure

The Standards Council of Canada’s report on supporting climate resilience infrastructure examines the standards associated with the most common natural disasters in Canada: flood, fire, and storm events. Furthermore, electricity outages caused by disasters often compound damages because most infrastructure is dependant on electricity to function. All these disasters have the potential to negatively impact wellbeing and the economy by increasing insurance premiums, provoking liability, diminishing credit ratings, degrading reputation and, of course, damaging infrastructure leading to a loss of service and costly emergency repairs. Property owners should consider which of these risks they are most exposed to so they can explore options to increase resilience through physical retrofits, improved preventative maintenance policy, and insurance-based solutions. Environment Canada’s weather risk criteria and Climate Atlas’ future climate projections per municipality are excellent sources to begin understanding your future climate risk.

Flood Risk

According to the Government of Canada, flooding is the most frequent natural hazard across the country and the costliest for property damage. FloodSmart Canada has consolidated floodplain maps across the country and resources for minimizing the impacts of flooding. 2018 saw the Canadian Standards Association issue new standards on basement flood protection and risk reduction. The Intact Centre for Climate Adaption produces useful reports and resources on climate adaptation. Their report, Ahead of the Storm, outlines adaptation measures that businesses can take to better manage flood risks:

- Plans and procedures: comprehensive emergency plans and funds complete with practice drills in place; including thorough tenant knowledge of emergency plans.

- Equipment and supplies: availability and accessibility of critical resources such as portable flood barriers, backup power and emergency lighting.

- Major retrofits: protection of critical equipment, especially electrical, communications and IT equipment.

Wildfire Risk

Wildfire can damage individual property and entire communities. Detailed fire behaviour maps can be found on the Canadian Wildland Fire Information System. FireSmart Canada has developed resources to help prevent wildfire risk for properties and communities. Adaptation measures to protect against wildfire risk include:

- Property maintenance: awareness and removal of vegetation and combustible material near the property.

- Simple upgrades to property: installation of non-combustible protection such as fences, ground cover, vent screens and siding-to-ground clearances.

- Complete upgrades to building: fire-resistant roofs, siding, windows, and doors.

Wind & Storm Risk

Storms and high winds can damage building exteriors, windows, and endanger tenants in extreme circumstances. According to the Standards Council of Canada & Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction, several design strategies can be used to reduce the risk associated with major damage from extreme winds.

- Large items like exterior HVAC systems, branches, and equipment are secured or moved out of danger.

- Installation of robust windows and doors, and closure and/or fortification of all openings to withstand extreme pressures.

- Structural design to ensure wind loads are properly transferred unto the foundation.

Dependency on At-risk Infrastructure

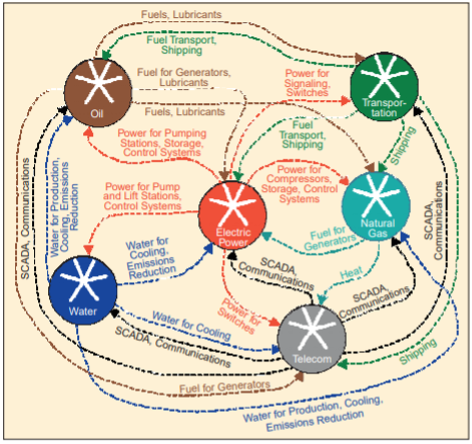

Many of these risks might lead to or coincide with a loss of service from critical infrastructure, such as the electricity system, water system, or transportation networks. Infrastructure is connected in such a way that a bidirectional relationship exists between all parts of the system and certain conditions can break the chain to cause catastrophic failure across the entire system (Figure 4). This is exactly what happened during the Texas winter storm, where the loss of the electricity grid led to cascading failures of many other systems.

Solutions exist to reduce this risk of interdependence, and typically involve designing more redundancy into the system, such as backup power. In 2016 the City of Toronto introduced voluntary minimum backup power guidelines for multi-unit residential buildings (MURB’s). The guidelines recommend at least 72 hours of backup power capacity, significantly more than the 2 hours the Ontario building code currently requires to facilitate evaluation. This additional backup capacity could give the electricity system time to recover. If similar extended backup power measures were common in Texas, it would have significantly reduced the risk of systems failure and may have saved lives.

Figure 4: Identifying, Understanding, and Analyzing Critical Infrastructure Interdependencies, (Figure 3. IEEE Control Systems Magazine, December 2001, Page 15. Rinaldi et al.)

Infrastructure Resilience

While increasing extreme weather may be inevitable, the severity of the impact can be managed. Risks can be identified, planned for, and adaptation plans implemented. The Insurance Bureau of Canada found that resilience planning in other countries proved to be 3-5 times more cost-effective than rebuilding after disasters, and the Institute for Catastrophic Loss Reduction estimated it to be 12 times more cost-effective in Canada. The Alberta government’s commentary of the 2013 floods notes the Manitoba Red River floodway saved over 100 times its construction costs in flood avoidance.

Resiliency means having a plan to mitigate risks before disaster strikes and allows systems to bounce back quickly following disturbances. As the saying goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

With contributions from Nathan Schaper, Sustainable Hamilton Burlington

Mantle Developments can help reduce your exposure to climate risk.

Contact us for help understanding the risks that climate change poses to your business and how to minimize them. We can help your team establish climate risk mitigation plans and develop comprehensive resilience strategies.